For the last 20 years, I’ve specialised in restructuring and insolvency law. I read a lot in my job. It’s an occupational hazard. Judgments. Skeleton arguments. Consultation papers and responses. Legislation – drafts (several) and final. Commentary on the same. Journals, articles and maybe the odd chapter or two from a text book. Thoughts on legal and market developments. Presentations. Reports. Law firm briefings. Much more besides. It’s not exactly reading for pleasure, although becoming absorbed in the detail of a point is something I enjoy.

Recently, I’ve been thinking – what exactly have I learnt from all my time spent reading? How has it shaped me as a person? Why don’t I need glasses yet? Actually, I think maybe I do – that or longer arms.

I know more law now than I did when I started out. Hardly surprising nor insightful. But that knowledge isn’t really just about specific rules, cases or sections – it’s more synthesised than that. What I know is a combination of separate thoughts about a range of issues that combine into a whole more complex than the mere sum of its parts. Time spent with all that endless, seemingly minor, distinctive detail over the years helps me now see the bigger picture. It provides context without obscuring what’s important.

I have become better at listening. Reasoned argument opens your mind to different view points – and the more you read with an open mind, the more you will take from it. Over time, this form of listening better enables you to draw parallels with similar issues, spot patterns or offer a new perspective to a problem. In my role, I like to think I generally work collaboratively with my colleagues – although there are exceptions. My focus is not so much on looking to persuade rather it is to offer support, act as a sounding board or stress test various options. The best experiences involve a healthy conversation about a legal problem where together we foster a deeper understanding – maybe even transform the question being asked. To do this effectively, it’s important to know when to yield. Only then can you absorb and offer a helpful redirection. If a junior lawyer has a valid point, they have a valid point. If a more senior lawyer doesn’t have a valid point, they don’t have a valid point. But how often does ego get in the way of accepting you are wrong? What does that teach the trainee? What respect do you then hold for the senior? What if you are that senior? What respect will people have for you if you always just have to be right?

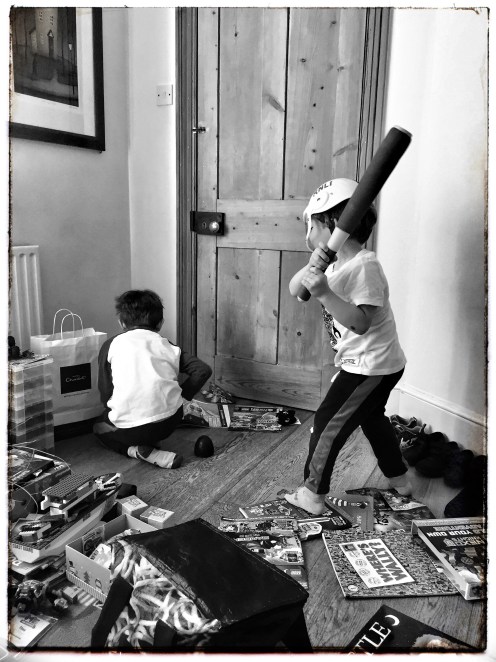

Yielding is hard. It can be seen as weakness or giving up. Far from it. It is a subtle – and supple – form of strength. Watch the tree bending in the wind or a cricketer catching a ball with soft hands retreating to absorb. This isn’t to say that you should always yield to an opponent – of course not (and clients don’t pay you to do that). But yielding plays a role even in adversarial combat – think of the martial artist who wraps around an attack and redirects the force. Yielding can be a useful tool. When done in the form of really listening, it can transform.

Reading about law isn’t unique in teaching you how to listen. All reading can do that, if you pay attention. But with its constant “on the one hand” and “on the other”, the side by side exposure to views you may support at first but then don’t and then do again – the opportunity is ever-present.